Two films would compete all year for Best Picture: A film by Richard Linklater called Boyhood, in which a boy comes of age in real time over a 12-year period, going up against a film called Birdman, supposedly shot entirely in one take, about an aging actor who doesn’t want to be a superhero anymore and just wants to make art.

I was Team Boyhood that year, though looking back, I don’t think either Boyhood or Birdman was a worthy winner. Instead, the movie that would stand the test of time and the movie I was obsessed with that year wasn’t even nominated. The year was 2014, and that movie was Gone Girl.

2014 was a time of great change; only very few of us realized it then. We were still climbing a mountain, and by the time we reached the top, there was nowhere to go but down. It was the beginning of both the Great Feminization and the Great Awokening that sought to reorder society to elevate marginalized groups and smash the white male patriarchy.

It was also the beginning of the two Hollywoods at a crossroads: making lots of money with superhero movies and IPs, and making art that almost no one saw or even knew about. The Oscars were caught there, too, though they chose the road less traveled, and that would eventually lead to a decline in ratings and the necessary jump to streaming, for movies and, for the Oscars, which have just announced they will be moving to YouTube in 2029.

I was ahead of the curve, you might say, back in 2014. I’m not sure exactly when my site went from being just an awards site to an activist one. Everybody had a loud microphone on social media, Black Twitter, Trans Tumblr, and a growing activist movement that meant we all had to look at how this new frontier was settling, who had power and who didn’t, who mattered and who didn’t. Who was to be protected and who was to be destroyed?

In the years I was advocating, I counted among my successes ushering in the first Black actress to win in 2001, Halle Berry for Monster’s Ball. She is still the only Black actress to win in the category.

I patted myself on the back for having overseen the first woman to win the Picture and Director awards, Kathryn Bigelow, and The Hurt Locker in 2009. Then, the first film directed by a Black director, 12 Years a Slave, released in 2013. But still, no Black director has won — even now as Oscar heads into its 98th year.

After all of their attempts to add new members, diversify, and install inclusivity mandates, the song remains the same. Power hasn’t really shifted so much as people of color were used as shields to protect the people at the top from the simmering unrest on social media.

2009 was the first year of the Obama administration, which had a significant impact on Hollywood, especially the Oscars. Obama is counted as among the new Left’s ruling class, joining Hollywood every year as he puts out his top ten lists and currently has a production deal with Netflix, which in turn donates generously to the Democratic Party. It’s all one happy, insular, perfect little paradise that has mostly forgotten that they still need audiences to show up if they want their films to be successful.

If you went back earlier than, say, 2009 and backwards in time, you’d see more powerful American directors helming big studio movies, like Clint Eastwood, Steven Spielberg, Ron Howard, and Robert Zemeckis. It was less about where they were born and more about the studios and their choices to put their trust in the best and most successful directors. It isn’t like that now, obviously, because the Oscars became disconnected from the economics of Hollywood.

What began to matter more was identity: how do those who win best represent the Hollywood elite?

Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire was the last movie to win because it penetrated American culture. That was 2008, before the Obama era. By 2009, The Hurt Locker would win without grossing more than $15 million, and almost no one had heard of it. It didn’t matter if audiences had seen it or not. What mattered was that Kathryn Bigelow was making history.

In 2010 and 2011, we saw prominent American directors who made big studio movies lose to international directors making smaller films. David Fincher’s The Social Network lost to Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech in 2010, and Martin Scorsese’s Hugo lost to Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist in 2011.

Ben Affleck made Argo but missed a Best Director nomination, which then meant he dominated the season and won everything. By 2013, however, we were about to enter what we called the “Three Amigos” phase. It went something like this.

2013—Alfonso Cuaron would win Best Director for Gravity.

2014—Alejandro G. Iñárritu would win Picture and Director for Birdman

2015—Alejandro G. Iñárritu would win Best Director for The Revenant, and Spotlight would win Best Picture

The one exception would be:

2016—Damien Chazelle, who would win Best Director for La La Land, and Moonlight would win Best Picture.

2017—Guillermo Del Toro would win Best Director and Picture for The Shape of Water.

2018—Alfonso Cuaron would win his second Best Director Oscar for ROMA, and Green Book would win Best Picture.

That Boyhood was the frontrunner in 2014 was an oddity, given that it only made $25 million. I was called upon to be an early advocate for the movie. I even drove out to Malibu to interview Patricia Arquette.

I had no illusions about my role in this. I knew I wasn’t being asked to go to parties with them and hang out with them because I was interesting or because I loved their movie. No, I was there to help them win.

Boyhood spoke to my generation, Gen X, probably more than any other movie. It’s all about ramblings on life, ruminations, and trying to find an identity. The whisper campaign at the time, likely put out by a rival publicist, was that it was “just a gimmick.”

Maybe it was a gimmick but so was Birdman shot entirely in one take. More or less. Linklater filmed Boyhood over 12 years, and many of us marveled at the commitment. But I have to admit my friendship with the publicist did color my reaction to the movie. I wanted it to win because I wanted him to win. But Boyhood was pretty good.

But Birdman spoke to voters in a way Boyhood never could. It wasn’t just the cinematic style of the film, all in one take; it was the subject. An aging actor choosing between selling out as a superhero for what audiences wanted and being an artist for no money.

It spoke right to the heart of your average Academy voter. But the romance of the Three Amigos was in there, too. They were in love with Iñárritu by this point, so any film he made was instantly elevated.

This scene was one of those most talked about for sticking it to film critics.

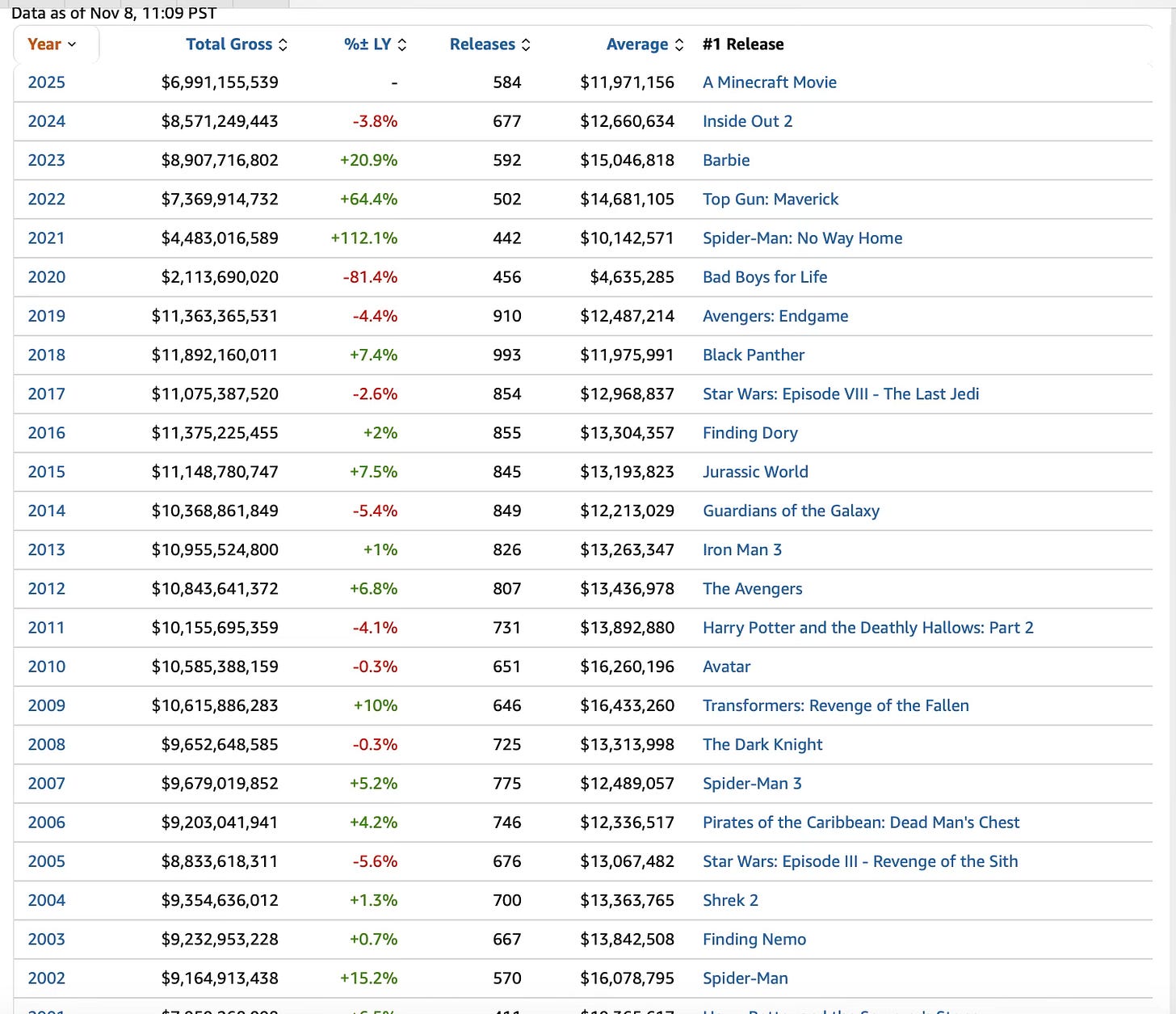

Birdman gave them a chance to remember their glory days before Hollywood was making ungodly sums on branded content. Their fanbase had been raised since birth to be just the kinds of audiences who would turn out to see movies like they turned out to eat fast food: fewer choices, expectations met. The kind of money they were making in 2014 was shocking.

$10 billion a year, with the number one film Guardians of the Galaxy, and here was the Oscars about to give their awards to Birdman, completely cut off from the rest of the country, and sucked into this insular bubble Hollywood became.

Birdman was their escape. They could pretend they still cared about art, just like the main character, even if they knew they were trapped.

It was kind of like the First Class section of the airplane vs. Coach. Or how McDonald’s makes money selling Big Macs but also offers salads to show they still care about your health.

These two Hollywoods would run on parallel tracks but exist in completely separate worlds until 2020, when the ship would hit the iceberg and the industry, along with everything else, would collapse. But we’re not there yet.

Another movie nominated for Best Picture in 2014 was Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper, which blew away the competition at the box office and probably was the movie most people outside the bubble thought should have won Best Picture. Why wouldn’t it? Don’t they reward success? No, they don’t. Not anymore.

The Academy probably would have wanted to omit American Sniper for obvious reasons, but how could they? Eastwood was still mostly a respected icon, even as his legacy was moving in the opposite direction.

The box office couldn’t be denied. It was a phenomenon.

American Sniper - $350 million

The Imitation Game - $91 million

The Grand Budapest Hotel - $59 million

Selma - $52 million

Birdman - $46 million

The Theory of Everything - $35 million

Boyhood - $25 million

Whiplash - $14 million

I wasn’t much of a fan of Birdman, but it did feature one great monologue by Emma Stone that telegraphed everything about to happen to the industry and society as we barreled toward 2020.

The internet and social media especially became a panopticon, which meant the people at the top, the ruling class, those who run Hollywood, were suddenly exposed. What mattered to them was being seen as good people trying to make the world a better place. They weren’t just celebrities; they were also activists with an online platform, and they had to use it to support the popular progressive causes of the day. If they didn’t, they would be called out.

Cancel Culture was in its early stages back then with the Tumblr blog, Yr Fave is Problematic, which called out celebrities for perceived crimes - thought crimes, cultural appropriation, sending the wrong message.

We had no idea what was coming next as we naively participated in this game of purging society of thought criminals. It was a way to purify and sanctify this brand-new frontier online. Who would be allowed to participate? Who should have a platform?

The word “canceled” came from Black Twitter as a kind of joke at first. Eventually, it became the catch-all term for a toxic invader that needed to be purged.

Women hadn’t yet risen to prominent positions of power, but it was just getting started. This would be what some would call the Great Feminization that would help explain how so much of American culture went woke, at least to hear Helen Andrews explain it.

There’s no doubt that Hollywood became feminized, and that’s probably what helped kill it and the box office, especially. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, after all. When you want everything to be fair and not to upset anyone, you end up with bland content no one wants to watch. Even if the two Best Picture contenders were still films that revolved around a straight white male, things were changing dramatically behind the scenes.

I loved the movie Gone Girl because I thought it told the truth about women in a way that almost no movies did in that era, the era of inoffensive art. Once we decided we needed to be good and to reflect goodness, the goodness of the utopia we manifested under the leadership of Barack Obama, and women were elevated because they were supposedly the future - movies were required to push that message too.

Gone Girl cut through it all like a hot knife. It resonates even now and has entered the pantheon because it didn’t pander or modulate. It presented Amazing Amy as the sociopath she was.

But the Academy could not make room for Gone Girl. In 2014, there were only eight nominees for Best Picture, at a time when the Academy had tried to expand its Best Picture slate to allow more than five. 2026 wants you to know it would be a huge mistake, but we’re not there yet.

Gone Girl is not a film for everyone. It was what I call a “kick in the balls” movie, meaning it was an affront to men, at least heterosexual men. Those kinds of movies don’t do well with the Academy, not then, not now.

Maybe it was a sign that I didn’t exactly belong in the world of Oscar blogging that, despite my singular efforts to push Gone Girl into the Oscar race, it only earned one nomination for Rosamund Pike in Best Actress.

Gillian Flynn, who adapted the screenplay, had been nominated by every other group heading into the Oscar race. Because Whiplash, a decent movie that launched the career of Damien Chazelle, was deemed an original screenplay by the Writers Guild but an adapted screenplay by the Academy, Gone Girl was ultimately dropped in favor of Whiplash in the writing category.

The frustration at the Academy over Gone Girl made me almost quit the Oscars. I felt they had overlooked what I knew was the zeitgeist movie, the one that penetrated culture and had become a phenomenon. The problem was I couldn’t quit. I was making more money than I’d ever seen in my life, and I was doing it from a business I’d built from the ground up, starting in 1999 with a simple HTML site.

I was working from home and could comfortably support my daughter. I felt like a success in all respects. Looking back on it now, knowing what I know about the people I used to call friends, the industry I helped build, and what they would all do to me ten years later, I probably would have been better off walking away.

I still think it’s embarrassing for the Academy to have left off the only movie people remember from 2014, but what I know about the Oscars is that you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.

#Oscarssowhite

There was a transformation afoot in the Academy throughout the “Three Amigos” era, but the key to it all was a hashtag called #oscarsssowhite. Even though I was known back then as what one might call a “woke blogger,” now, I was advocating hard for women and people of color, and I believe I influenced how the race turned out, especially in the Obama era.

I pushed hard to boost the career of Ava DuVernay, whose film Middle of Nowhere had won Best Director at Sundance and was coming into 2014 with Selma, a biopic of Martin Luther King, Jr. I believed I was doing useful work, that DuVernay and others could not have gotten a boost without me to scream loudly about racism in the industry and force change. DuVernay herself thanked me at a Wolf of Wall Street screening the year before. So at least she noticed.

I wanted her to make history and thought she deserved it, but getting the voters to recognize Selma was a heavy lift. For whatever reason, the movie did not resonate with voters, and though it would barely squeak in under the wire as a Best Picture nominee, it would get only one other nomination, for Best Song.

The Academy back then was caught between worlds. Their demographics were roughly 94% white and 77% male in 2012. That would remain unchanged until 2016, when they began adding members by the thousands, with only skin color and gender as requirements. That would have unintended consequences later, but we’re not there yet either.

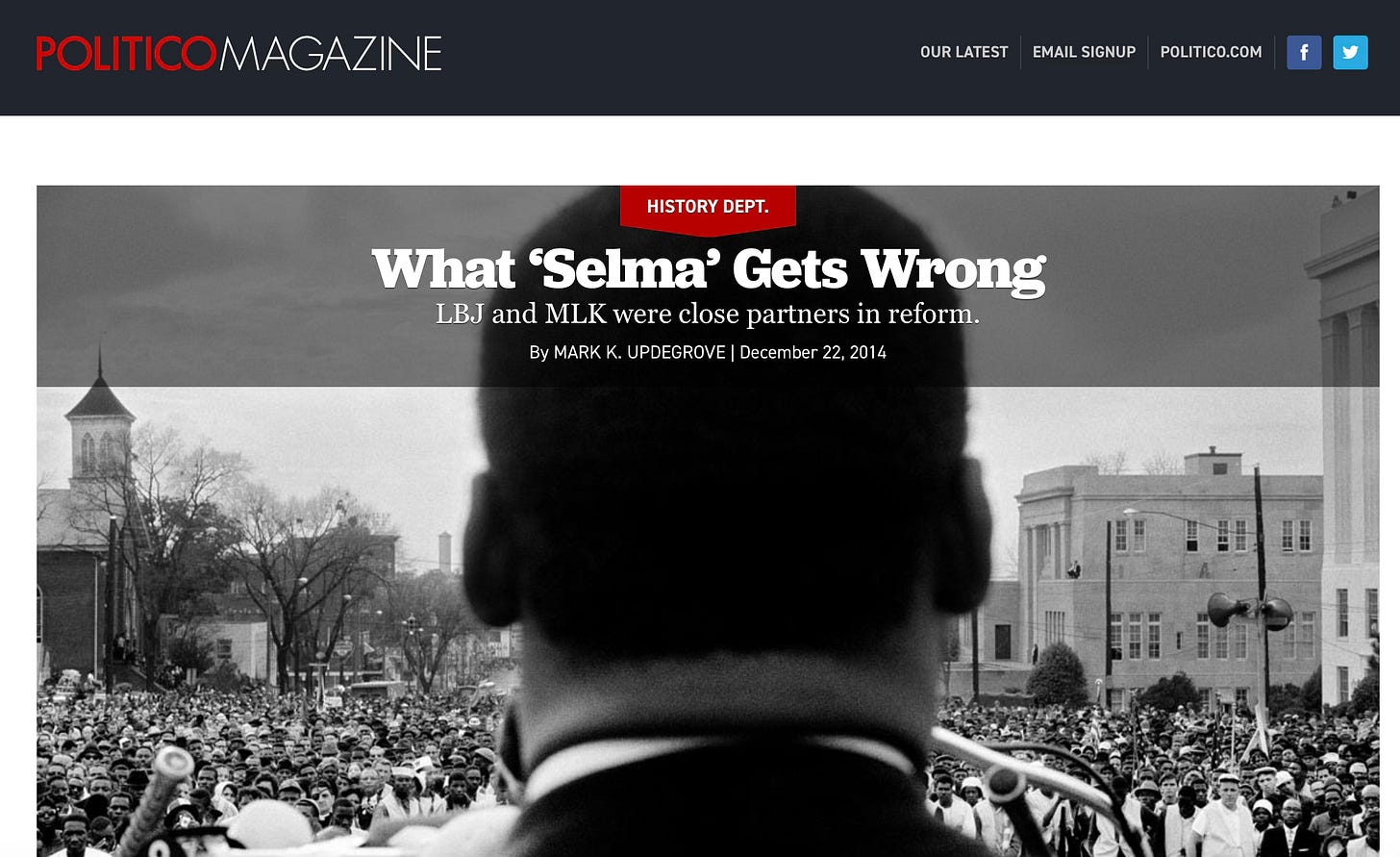

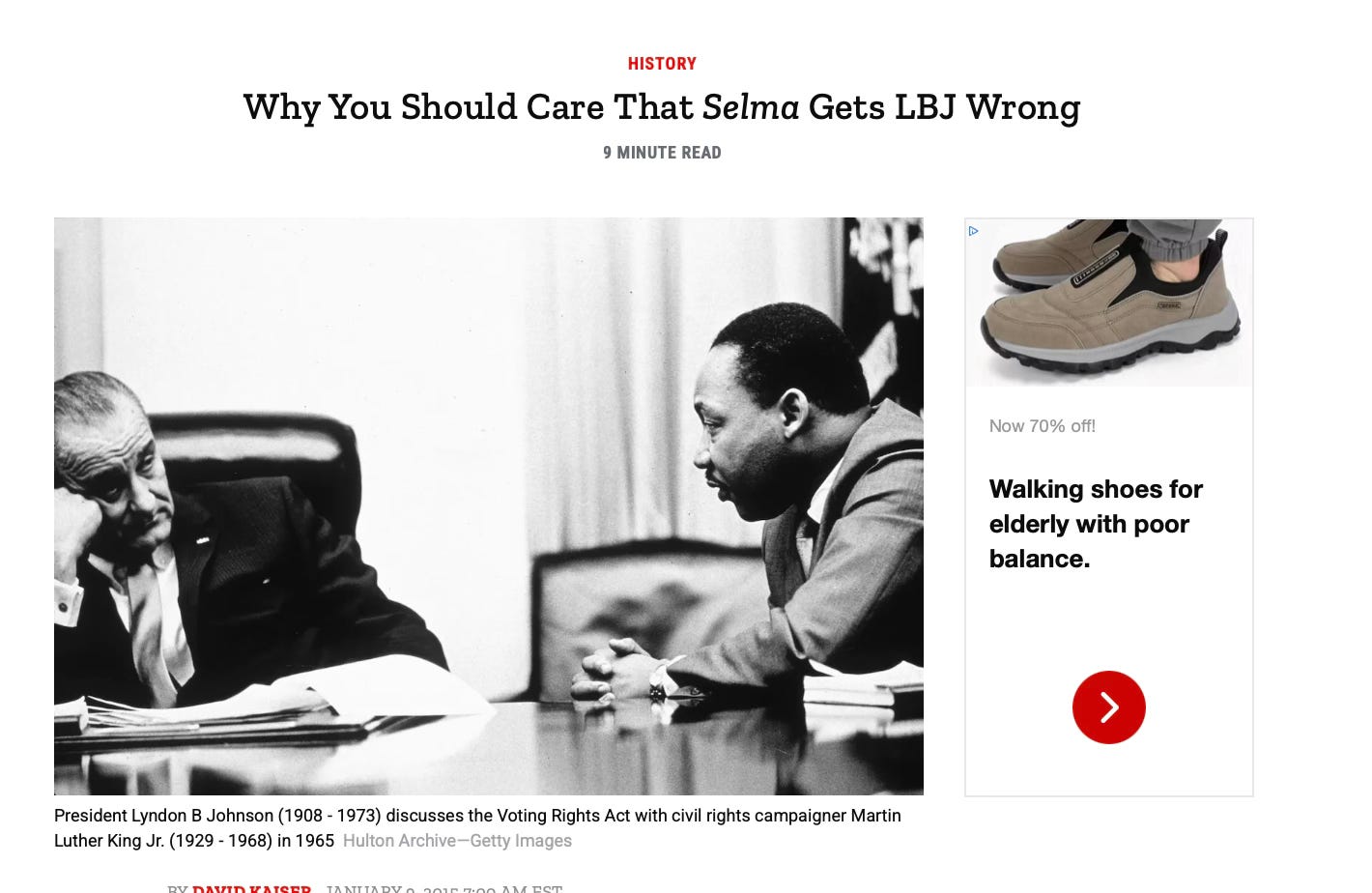

This wasn’t an industry that was ready to elevate Ava DuVernay as an influential filmmaker in Hollywood, at least not with Selma. There was some public dust-up over the film’s depiction of LBJ, something no writer or critic would dare to challenge today in the post-cancel culture Hollywood.

It made several of them mad enough to write defensive essays.

Just imagine Politico, TIME, or even a major network today putting out such stories on the eve of Oscar voting. That mostly gave voters an excuse to ignore the film, or to vote for it only for Best Picture. I had been pushing it as hard as I could that year, but in the end, that didn’t have as much impact as a Black woman and her hashtag, #OscarsSoWhite.

That’s because when the Oscar nominations came out, all of the acting nominees were white.

What we all believed back then, or the low-hanging fruit of the time, was that they all had to be racists. Even if deep down we knew they weren’t. They were the Good Liberals, after all, who voted for Obama. But it wasn’t enough. There had to be representation of people of color, and April Reign made it now a much bigger story, one that publicly humiliated the ruling elite who wanted to project goodness, then and now.

Because social media allowed us to hurl anyone into the public square and humiliate them, we began to construct a system that would ultimately paralyze Hollywood, both in the movies that got made and in how critics and bloggers covered them.

I was headed straight for a brick wall, and I had no idea what was coming. I didn’t know that I would be the one person who could not go along with how things were changing, the one person who would push back, and the one person who would become an accused and condemned witch at a time of mass hysteria and cancel culture purges. It would not be for anything I did, but for things I said.

I could not have known that in 2014. Back then, I just felt like a woman with a purpose, to help elevate women and people of color into the Oscar race. The industry invited me to the Oscars and parties, affording me proximity to fame and power. But they were threatened by April Reign and #oscarssowhite, so much so that they began to force change on the backend. It would take a while, but by the end of it, no one would recognize the industry or the Academy.

My problem was that I couldn’t keep my mouth shut. I felt compelled to tell the truth. I felt compelled to fight against something I saw consuming our culture and ultimately destroying it.

The Oscar Race

Boyhood was winning an unprecedented number of critics’ awards heading into the race. By the end, it would take both New York and LA, along with the Critics' Choice, the Golden Globe, and the BAFTA.

Birdman, however, would catch fire with the guilds, something almost none of us saw coming. Except my long-time friend, Hollywood-Elsewhere’s Jeff Wells. He loved Birdman and had been pushing it and predicting it all season. So when it caught fire at the Producers Guild, then won the Directors Guild and the SAG, we knew it was all over but the shouting.

When a movie wins all of the guilds like that, there is no chance it loses the Oscars. Movies like that are rare, but they still happen, like Oppenheimer.

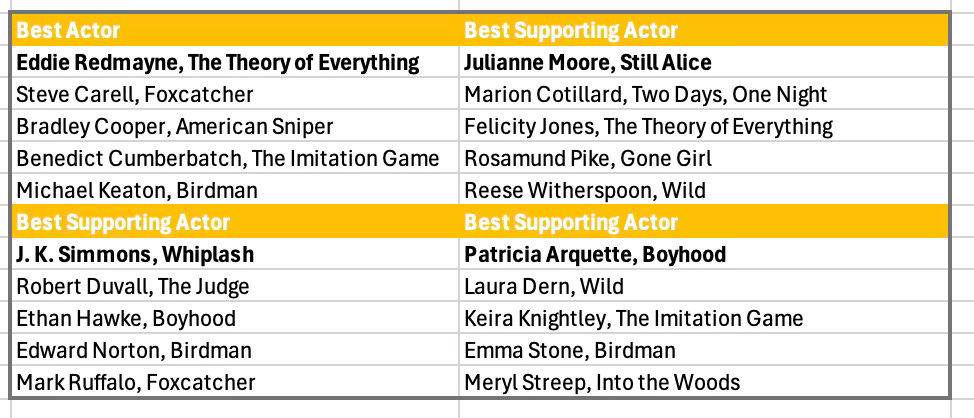

Some people kept clinging to the idea that Richard Linklater might win Director or Boyhood might win Picture, but no. The race was over by the time we got to the PGA. Patricia Arquette would be the sole winner for Boyhood, Best Supporting Actress.

The Best Actor race seemed to be Michael Keaton’s to lose. He seemed to really want it and had every reason to believe, even if Birdman didn’t win Best Picture, that he’d at least win Best Actor since he was the whole movie. But that’s not how things went. Eddie Redmayne playing Stephen J. Hawking would prove irresistible to Oscar voters. There was no way a Birdman could beat a Hawking.

Best Actress became Julianne Moore’s to lose. In Still Alice, she played a woman afflicted with Alzheimer’s.

She makes a plan for her own suicide when the time comes, but then, once afflicted with the disease, she forgets all about the plan. It might be the most depressing movie ever made, but it meant that Julianne Moore, who seemed very overdue at the time, finally won. It wasn’t her best performance, that would be in Far From Heaven, but you take what you can get.

Best Supporting Actor went to JK Simmons for playing the taskmaster drum teacher in Whiplash.

It was quite a performance, and the voters loved the movie. Chazelle would be back in two years with La La Land.

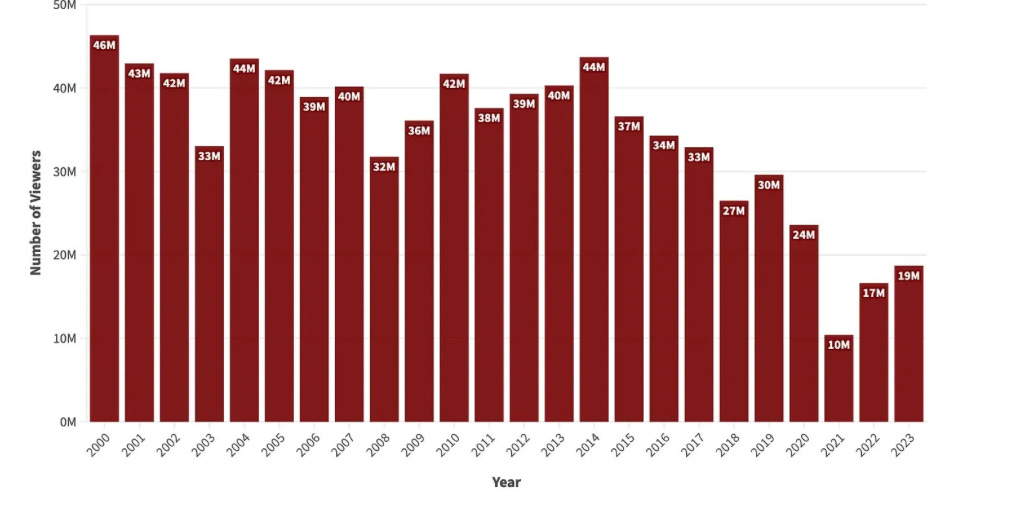

The ratings back in 2015, for the Oscar year of 2014, were pretty good. They hadn’t yet utterly and completely collapsed like they would later. Probably, this was the first year they began to steadily decline to 37 million. They were just 19 million this past year.

I came away from that year thinking the Oscars were trapped between awarding films with critical acclaim and awarding films that reflected who the voters were, but neither of these movies Boyhood or Birdman penetrated outward as Gone Girl did. I remember how devoted my site was to that one movie, and seeing it all but shut out was probably a good sign that I had very little influence after all, even if I wish I did. I seemed to be able to boost only those movies that Academy voters also liked.

I do still watch Gone Girl probably once a year. Whenever I do, I rarely think about the Oscars it didn’t get. The art, the movie, that’s what matters more. Lucky for me, I had a real life too. My daughter Emma was still at home and hadn’t yet left for college, and in 2014, there was a furry new face in our lives.

A Dog Named Jack

I was lucky in 2014 to meet one of the best friends I’ll ever have. I was driving to the Telluride Film Festival with my daughter and her friend. We pulled up to a gas station near the Four Corners - Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah - and a small puppy approached me with what appeared to be a smile on his face. He wanted something to eat. I melted on the spot. He looked wolf-like with green eyes. But it was his gentle nature that I could see in his personality, and I knew I couldn’t leave him there.

He was unusual because he looked like a red border collie, but he was a mixed breed that seemed obvious. We were near a reservation, and it was not uncommon for abandoned puppies to turn up at gas stations.

So I went inside and told my daughter and her friend to buy dog food, since we’d be taking the dog. But when I turned around, he was gone. A woman came up to me and said she saw him hide under a trailer. She coaxed him out, and within minutes, he was in our back seat driving with us to Telluride.

We brought him to the Airbnb, which had a converted basement that functioned as a bedroom with a shower. Jack wasn’t exactly potty trained, so we had to make sure he was taken outside or that we’d have to clean up his mess. At the moment, we weren’t sure who was going to take Jack. Emma’s friend wanted him, but her parents said no. She sobbed, begged, and pleaded. A woman who saw him on the street also said she’d adopt him.

But after a while, it became clear to me that Jack was mine. He would be my dog, my buddy, my best friend. A dog is a big responsibility, my sisters warned. I’d had to give one away to my mom years before because a boyfriend of mine demanded it. Even though that dog ended up having a great life, I always felt guilty about it, and I knew I’d never do that again. So when my boyfriend at the time, a guy named Rick, demanded that I stop paying so much attention to Jack because Jack was nervous about going to his apartment, I broke up with the boyfriend instead.

Rick was a complicated guy and would end up dying of a drug overdose in 2020 due to the loneliness of lockdowns, but the last time I saw him was because he made me choose between him and my best friend.

It’s eleven years later, and Jack is getting old. He can’t run anymore. He can’t really walk that far, though he wants to. His breathing is labored. He has snow on the mountain, his red fur is turning gray. His eyes look lost half the time and I think he sometimes forgets where he is. I know I’ll have to grim up and bear this last part. I’m trying to remember to enjoy whatever time I have left with him. We’ve been through so much together.

I always thought he felt the call to the wild, but had to spend his days on a leash, and how boring that must be. He often lies down several times during even our shorter walks. He needs to rest. I can barely think of life without him. He goes with me everywhere, along with my other dog, Luna.

So when I think about 2014 and what it meant to me, other than the time I still had my daughter living at home, it is the gift of finding my puppy, Jack. My sweet boy. My best friend.

I don’t think about the parties or the celebrities or even the movies. I barely remember the Oscar ceremonies. After a while, it began to feel like a job. The studios had complete control over the bloggers because we needed and wanted the money. It seemed great for a while, but then it didn’t. Then it began to feel like a rigged game.

No, what stays with me are the memories I will treasure—camping at Leo Carillo beach with my daughter. Watching my puppy, Jack, run through a field when he still had the youth and energy to do it. I will remember the time spent watching my dearly departed father play the drums when he was still alive. I will remember baking vegan pies for a guy I was dating, how they slid off the seat and fell onto the floor of my car, but how he ate them anyway.

I will remember the time spent with my daughter when I had no idea she’d one day leave home, and I’d only see her twice a year. These are things I see in pictures on my computer. They are memories I know one day will fade. But that’s the part of life that matters. The rest of it doesn’t. Social media wars, stupid gossip, even cancel culture doesn’t matter, and the Oscars most certainly don’t, not compared to the other stuff, the real stuff. People, beloved pets, traveling to places, creating real memories.

2014 was a long time ago. We all thought that the culture we built, the rules we put in place, the way we saw ourselves and our country would last forever. But it didn’t. Nothing is the same now, especially not me.

I’m not even the same as I was when I started this podcast memoir back in 2019. I’m not the same as I was in 2020. I have changed and changed dramatically and so has the Oscars. I did not know heading into this that there would come a time when people I used to know would tell me there is only one way to be, one way to think, one way to speak, and if I didn’t follow these dictates, that would be it, the end of friendships, of business, of being invited to parties and the Oscars.

I still don’t know what the future holds for the website I started 26 years ago, but the industry I see now isn't one I want to be part of. The people turn out to be shallow and cowardly in the face of tyranny, not from Trump but from themselves.

The thing is, I didn’t know how to do the other thing. I didn’t know how to lie and stay silent. I couldn’t be someone who abandoned a friend over politics or anything else. I had no choice but to do what I’ve always done, write the truth and speak from the heart.

I still love movies and hope the industry can revive itself. But if it doesn’t, at least I got to be there when the getting was good.

//